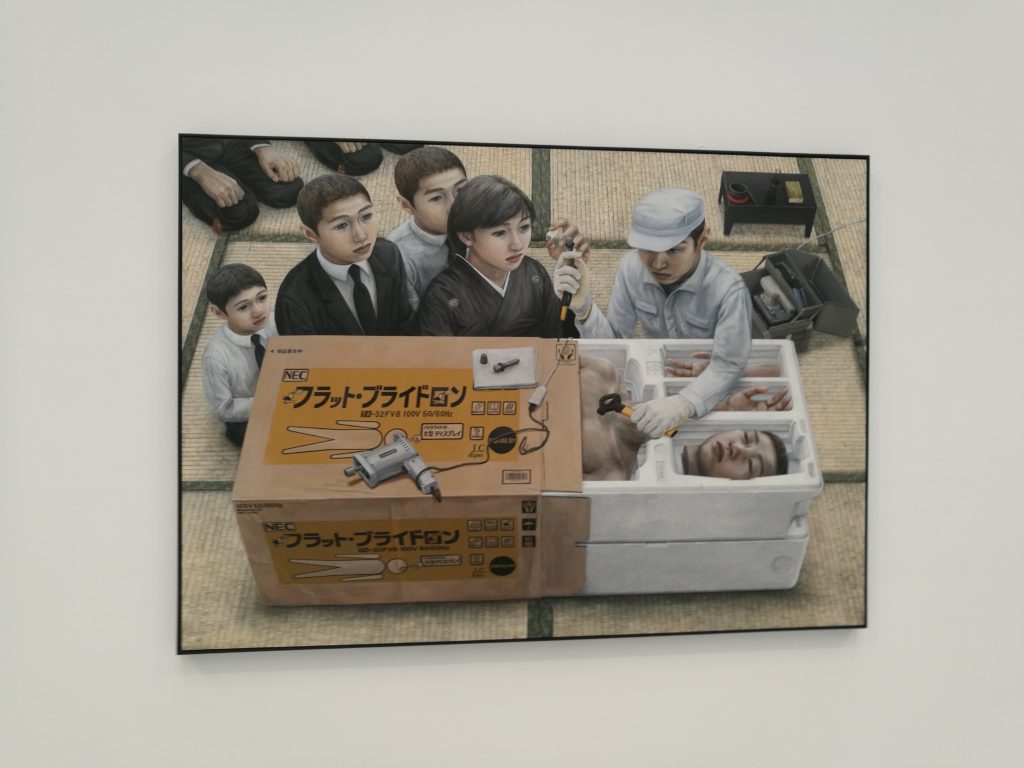

Self-Portrait of Other is a revelation for all those who devote their vital time to greasing the wheel of labour exploitation without questioning the system. Just as a psychic gifted with an extraordinary mind, Tetsuya Ishida’s, the Japanese painter, portraits reproduce a realistic view of what could have been considered a dystopia come true: the return to slavery in the 21st century. Salarymen exhausted by their work until they are broken into pieces and lonely insect-looking boys in the purest Kafkaesque style. All well surrounded by an atmosphere of gloominess that is not pleasant to the eyes but that is particularly touching.

In order to understand better the message it may be useful to look at Ishida’s biography, even if he denied any correlation between his paintings and himself. The Japanese embraced his art studies against his parents and teachers’ will, who had visualized for him a career as a teacher or chemist, in a period of economic turbulence in Japan. Similarly to many youngsters of our days, the artist reached the job market little after the explosion of the financial bubble of the 90s, a direct consequence of the economic miracle in Japan. All this left a deep imprint in Ishida’s work as can be seen throughout the entire exhibition. It does not seem trivial, then, that Ishida’s first retrospective outside of Japan takes place in Spain, a country with 30% of youth unemployment and wages way below the necessary to live. The exhibition seems to actually reproduce the daily lives of a number of Spanish youngsters.

The discerning visitors will notice a hair-raising parallelism between Ishida’s works and the theories of the Korean philosopher Byung-Chul Han. The interrelation is such that Ishida’s paintings may have served to illustrate some of his books about neoliberalism and self-alienation, except for the fact that those were written almost 20 years after Ishida’s death. These two thinkers of nowadays have many meeting points that can be discovered through the exhibition, but the truth is that we will never know whether Ishida imagined all those different readings from his work since he died pretty much before internet and smartphones contributed to alienation 2.0.

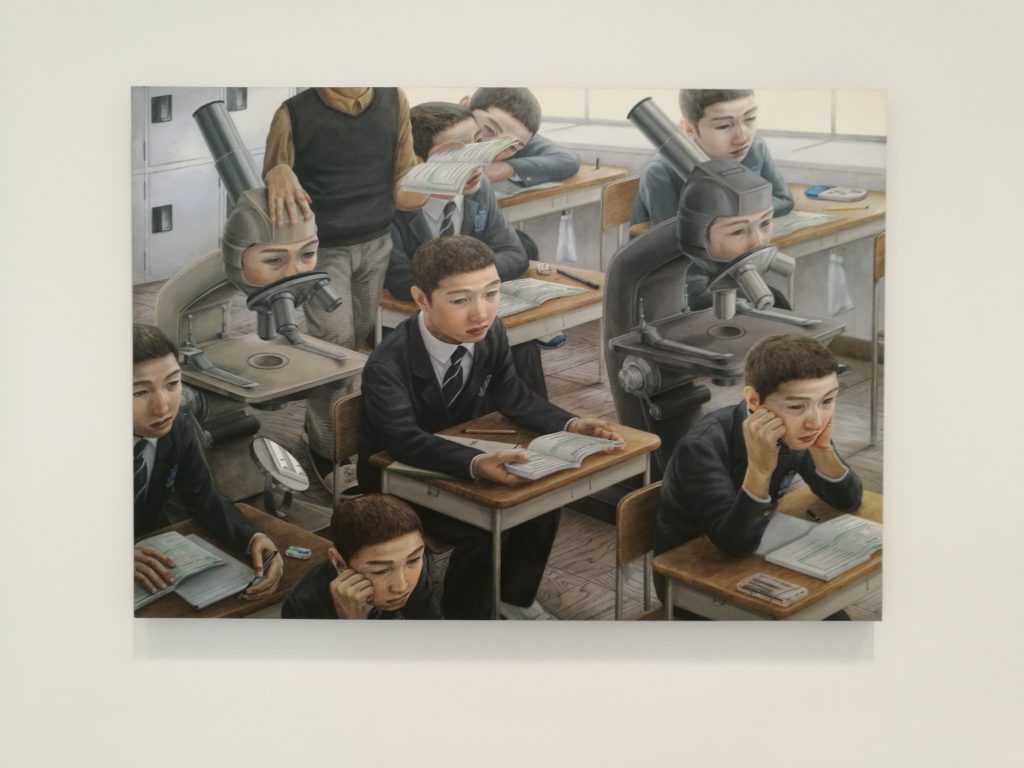

The most confluent of those points may be the strong critic, or parody in the case of Ishida, to the seeking of homogeneity in the society. In his book The Expulsion of the Other: Society, Perception and Communication Today Byung-Chul explains the importance of uniformity to favour the economic system: consumers with similar needs and tastes lower production costs and increase the profit of the system. Following the philosopher’s perspective, the artist’s illustrations of clone-looking boys and businessmen seem a savage critique to neoliberalism. On the other hand, when drawing those stories Ishida seemed more concerned about portraying a society that raised children to fit into a system from which he was an outsider.

As a last note, another relevant aspect from Reina Sofia’s retrospective, that can be extrapolated to the rest of Ishida’s work, it is the absence of the feminine figure at both school and office. The woman is usually portraited as a mother or wife at home that worries and cares for her destroyed husband. The reasons why Ishida portrayed women in this way remain unknown today despite the fact that we can ascribe this to a traditional mentality. On the other hand, it may also be a starting point to reflect on the sexist mentality that brings to portrait only men spending long hours working and how this has changed since Ishida’s leaving.

Ishida’s Self-Portrait of Other is available in Palacio de Velazquez, Museo Reina Sofía, el Retiro, Madrid till the 8 of September.